“Street Aesthetics” and “Light and Objects”

Miki Desai, as an undergraduate student, curated an exhibition of twenty-five large black & white blow-ups ranging from 40" x 40" to 120" x 80" on themes of "Street Aesthetics" and "Lights and Objects" at the Sanskar Kendra, Ahmedabad, 1974.

Portraits of Traditional Dwelling and its Holistic Environment, Gujarat, India

Miki Desai held an exhibition of black & white photographs titled, "Portraits of Traditional Dwelling and its Holistic Environment, Gujarat, India" in an international symposium, "Traditional Dwellings and Settlements in Comparative Perspective" at the University of California, Berkeley in 1988. These photographs of Indian Built Environments have also been displayed at the University of Arizona, Tuscon, the University of Texas at Austin, and in a Street Show in New York City and in Ahmedabad.

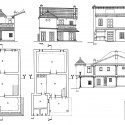

Indian House Form and Culture: Traditions of Gujarat

"Indian House Form and Culture: Traditions of Gujarat" was an Exhibition held at The Rietberg Museum, Zurich, Switzerland, May-Aug 1990. The Exhibition consisted of 150 to 200 of Miki Desai's photographs and included several measured drawings, maps and accompanying text. It also had 7 large-scaled, well-detailed wooden models, an audio-visual show, and the publication of a catalogue in German. This was perhaps the first such exhibition in Europe.

European Exhibition "ILL WHY”

Miki Desai contributed a model and a chapter in the European exhibition "ILL WHY" at the Deutsches Hygiene Museum, Dresden, Germany. The exhibition traveled to six other German speaking countries also during 1995-1998. The chapter in the catalogue deals with the non-medical concepts of illness in Indian philosophy, including the theory of Karma. The model is a 20-scale, large replica of a traditional temple in Kerala, Southern India that has a high symbolic value for curing illnesses. About ten carpenters made the model under supervision. The production process followed the system of construction in a miniaturized form.

Image and Imprints

Kaleidoscopic View of Indian Heritage:

I have seen the world passing by, I have seen and met good people and not so good ones, I have seen inspiring people and the dull ones, I have seen bad building and good buildings, I have been in good spaces and bad ones, I have seen beautiful walls and also seen walls on which people urinate, I have gone to urinals which stink like hell and are not fit for even animals, I have seen staircases full of red colored paan pichkaaries, I have gone to beautiful buildings and have been in wonderful spaces, I have gone to terrible buildings, I have been to too many depressing buildings and spaces, I have been to places and spaces that give me the joy of being there, I have seen some beautiful trees and landscapes, I have been to too many unkempt places; I am ashamed to show you the bad things we do to our living environment, towns, cities, roads, footpaths; have you not seen them bad things? Have you not been a part of “this mad traffic, the rush?” Your heritage and pride in the ‘things India’ is engulfed in the “who cares” syndrome, I have stopped the world and the time for you to revisit it, I have, I have, I have; I have selected only the good things that sit within all those bad things for our reminiscence; do come and visit your wonderful world; I have even sprinkled it with some arts farts things…..it is the exhibition “Images and the Imprints” of the world that has passed by me. Sanskar Kendra, Ahmedabad, 2012 and CEPT University, Ahmedabad, 2015

Kerala and Gujarat Mosques: A Comparative Study

Islamic architecture made its presence in the beginning of the 13th century in India. It propagated from Arabia to Persia, through Central Asia and eventually to India where the Muslims invaded and dominated the country. This imposed Muslim domination survived over 600 years in Northern India and concluded with the Mughal dynasty. By forcibly expropriating eligious sites, schools and colleges, they used the old building material to construct mosques in the beginning. Home to more than 300,000 active mosques, India has more mosques than any other country in the world. As we move from North towards Southern India, various architectural styles emerge starting from Tuglaqi/Qutb Shahi around Delhi, Maru-Gurjar in Gujarat and Rajasthan, Bengal Roofs in the Eastern regions and Bahmani in parts of Karnataka and Hyderabad. The exploration of architectural styles in the stone architecture of mosques is last seen in Gulbarga Mosque, Bijapur, south of which one finds mosques in timber in the same style as the regional architecture. By 17th century, the mosque architecture in India had stabilized with big domes, arched gates, prayer halls and high minarets becoming the essential components of the mosques. Typically, a mosque comprises of a square or rectangular plan with an enclosed courtyard, covered prayer hall consisting of a qibla wall (towards Mecca), mihrab and minbar (a raised platform from which the imam addresses the congregation). The Persian prototype of mosques was imported to India, where in the Persians inherited “Iwan” from ancient palace architecture as a square shape framing a large arch opening, inside of which is a vaulted half-exterior space. The Iwan thus became a vocabulary of Indo-Islamic architecture. The exhibition explores the forms of mosques in Kerala and Gujarat based on climate, materiality, and construction systems as well as characteristics of articulation and embellishment along with socio-cultural aspects by comparative analysis of plans, sections, elevations, elements, and articulation as found in the two regions. Aga Khan University, London (2018)

From My House to Your House

The development of the history and theory of Indian architecture has focused on the classical edifices of the subcontinent with the recent inclusion of colonial architecture. There has also been a range of publications on modern architecture as well as hagiographic books on the successful contemporary architects. Inadvertently while pursuing the goals of modernism during the post-independence period, Regional Identities were almost entirely pushed aside. Although there are passing commentaries on regional traditions, detailed study and documentation of these traditions have never been a major concern of scholars or schools of architecture. Research of serious and accurate nature in this field is sporadic and has reached neither the academics nor the policy makers. In absence of methodical surveys, listing and a body of knowledge regarding the regional architecture, the task of drawing a sensible blueprint for the conservation of this disappearing heritage legacy remains at bay. It is a lacuna that needs to be redressed. With the above as a concern-worthy background on Indian traditional, colonial, and modern genre of architecture; the author has been surveying and documenting them for 45 years. The resulting documentation has yielded close to 40,000 images and 200 manually drafted measured drawings. This documentation has been an academic endeavour of a consistent nature. The author has researched many aspects of this architecture and has written a few books based on this. The University of Moratuwa, Colombo (2016), the India International Centre, New Delhi (2020) and the Bengal Institute, Dhaka (2023).

Wooden Architecture of Kerala

Among the rich heritage of building traditions in India, one of the oldest and continuous building traditions in the world, wooden architecture of Kerala is unique. It is significant for its use of materials, craftsmanship, tectonics, and its connection to ancient canonical literature on architecture. Its homogeneity and continuity are unusual and have been nurtured by the regional arts and crafts. Its distinct architectural language has its own intonations and symbols creating a special aesthetic experience. Typological contents of sociocultural nature of Kerala’s wooden architecture are a stand-alone genre that has given both the secular and religious architectures for over 300 years. The exhibition explores these unique aspects of Kerala's wooden architecture, which is deeply rooted in religious and secular customs and shaped by geo-climatic forces. Its multi-disciplinary approach links the various ethnic groups residing in Kerala, and the mutual adoption and adaptation of construction systems within migrant groups. Decoration and meaningful articulations bring about the character and personality of different sub-regional examples. A dominant spatial element and the facade typify each dwelling type. Upon scrutiny, one finds that most of the aesthetic nuances, though rendered by artisans; have resulted from people's daily actions and involvement in life. This has resulted in an inseparable relationship of the built environments and daily life. Wood being the prime material of Kerala, the craftsmanship of the carpenters as well as traditional treatises have contributed to the exclusive architectural expression of secular and religious architecture. This exhibition celebrates this genre, especially in view of the fast change in traditional ways of building as impacted by the modern. AVANI Institute of Design, Kerala, 2023